WiFi-Hog: From Reaction to Realization. By Jonah Brucker-Cohen

When technologies are first introduced, hype usually follows. The hype naturally dissipates over time, but when news begins to spread about how people are using the technology, the hype machine begins to resurface. When I first heard about wireless internet (or 802.11b) back in early 1999, I ignored it. This was a technology that seemed very far off, as no computers were yet equipped with wireless receivers (except a few Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs)). I heard about people using the technology in classrooms and hospitals, with very particular applications that seemed too particular for any mainstream adoption. A few years later, wireless internet (now affectionately called “Wi-Fi”) began to resurface as reports of projects and public community networks began to sprout up. Wireless was becoming cheap, pervasive, and simple to implement.

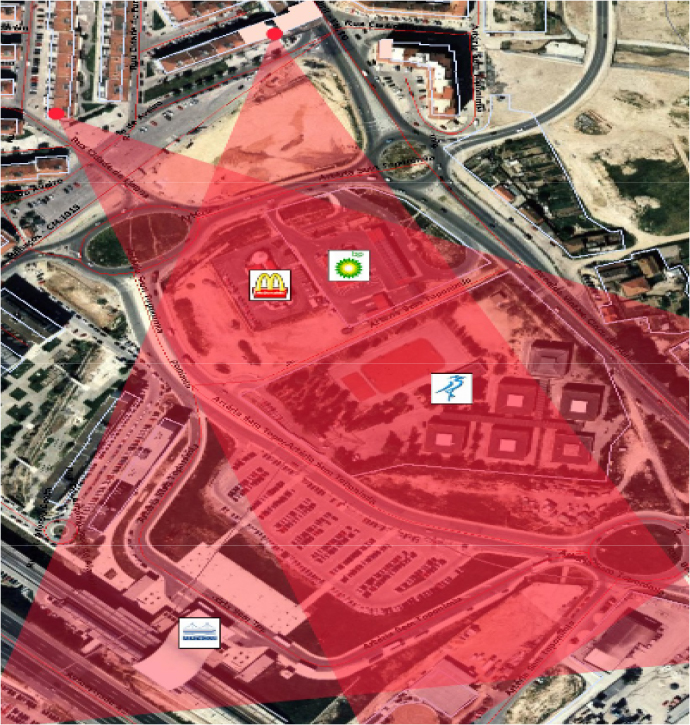

After hearing about the hype and projects, I began to notice something else that was happening in and around wireless nodes and their deployment. In August 2002, Slashdot ran an article about “Starbucks vs. Personal Telco Project (PTP)”, a battle that was quietly taking place in Portland, Oregon’s Pioneer Square. This was a challenge over public obstruction of wireless space, where corporate signal was out-blasting the pre-existing community signal. PTP had two 2 T1 connections with off the shelf routers setup providing free wireless access to anyone in the square. A few months later, Starbucks who partnered with T-mobile, set up in-store satellite Internet access that broadcasted on Channel 1 within the store and around the square. Channel 1 is the default connection found by most consumer wireless cards. As a result, since Starbuck’s signal was stronger and its connection speed was faster than PTP, the once free network that pervaded the park had to close down. The struggle over claiming ownership of public spaces with wireless nodes was in full swing. On a trip to the NYC Wireless headquarters last year, I heard a story about how Verizon (a major telecommunications company in NYC) had started to put high-power wireless access points (APs) on the tops of all of their pay phone booths in the city. These blanketed every block of the city and were only available to customers of Verizon’s DSL service. NYC Wireless had set up a free node from their office which was meant to reach the street below, but Verizon’s corner payphone node was interfering with it. The problem was further reaching than I thought.

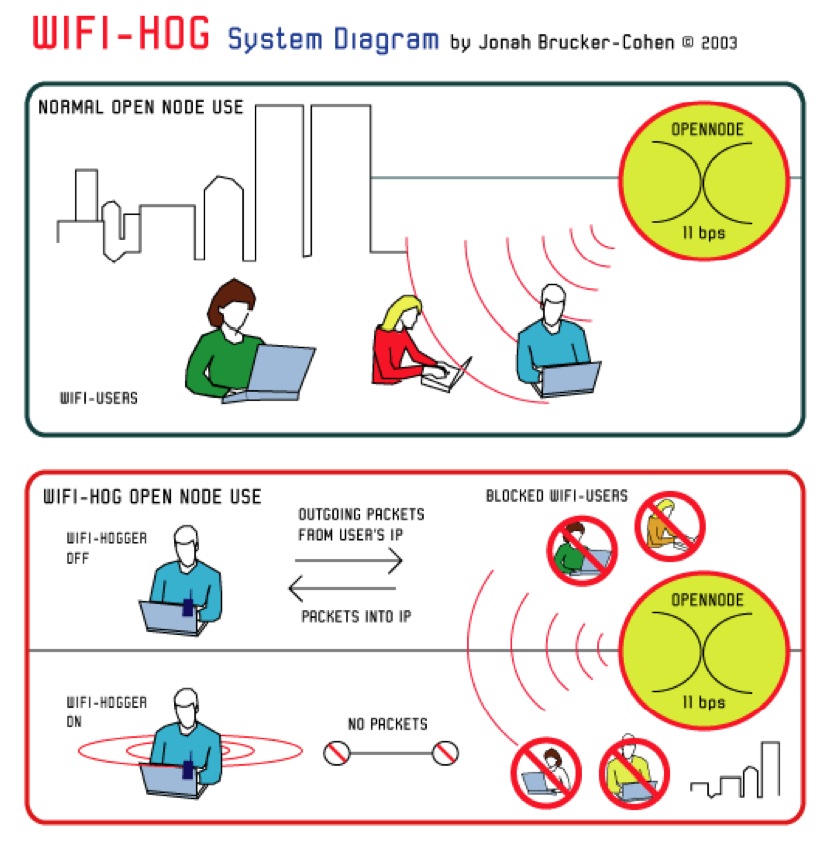

Wifi-Hog, System Diagram, 2003.

In 2003, I began working on a project called “Wifi-Hog” that was a direct reaction to the claim of ownership that corporations and individuals were placing on public wireless space. The project consisted of a laptop connected to a Portable Video Jammer (PVJ), and some custom circuitry that communicates to software on computer. The software was comprised of a packet sniffer (such as Carnivore) and wireless stumbler (such as NetStumbler which allows the software to find open networks) which monitors incoming packets from an open node. The idea was to only allow traffic originating from the Wifi-Hogger’s IP address to access the network, otherwise the PVJ is switched on, blocking others from connecting to the open node. Since most Wi-Fi networks operate on the un-licensed 2.4 GHZ band, jamming this spectrum is not illegal. There are over 100 websites that advertise and sell the PVJ, so finding one was relatively easy.

Wifi-Hog, Jonah Brucker-Cohen, Demo View, 2003.

Wifi-Hog is a tool that enables control over a specified network by someone who is not the network’s administrator and looks specifically at what happens when these seemingly open networks are made exclusive and competitive. Since these networks exist as private, public, and corporate monitored services, there is also confusion about rights ownership over networks in public spaces, thus Wifi-Hog is specifically reacting to the lack of an “Acceptable Usage Policy” of wireless networks. As mobile technology has entered public space and brought private conversations and interactions along with it, an interesting rift was forming between what is deemed acceptable usage. In a sense, Wifi-Hog exists as a tactical media tool for controlling and subverting this claim of ownership and regulation over free spectrum, by allowing a means of control to come from a third-party.

As mobile and wireless devices become more ubiquitous, free and public wireless nodes have gained high penetration. Free nodes are popping up in public parks, airport terminals, libraries, schools, and other venues worldwide. In addition to sanctioned spaces for the nodes, private nodes without encryption are leaking from offices and houses onto city and rural streets. Activities that exploited and actively seeked out these networks began to materialize. Some examples include the WARchalking and WARdriving phenomenon (where you search for open nodes on city streets and mark their location with chalk) and artist interventions like “Noderunner” and Blast Theory’s “Can you see me now?” which integrate urban street players with wireless connectivity. As the networks grew, especially in dense urban spaces, signals from private, public, and commercial (or paid) nodes began to interfere with each other. This spectrum overload brings up even more questions about how jurisdiction of signal is defined and who has precedence over others.

Invasion of Public Space by Corporate Wireless Networks, 2004.

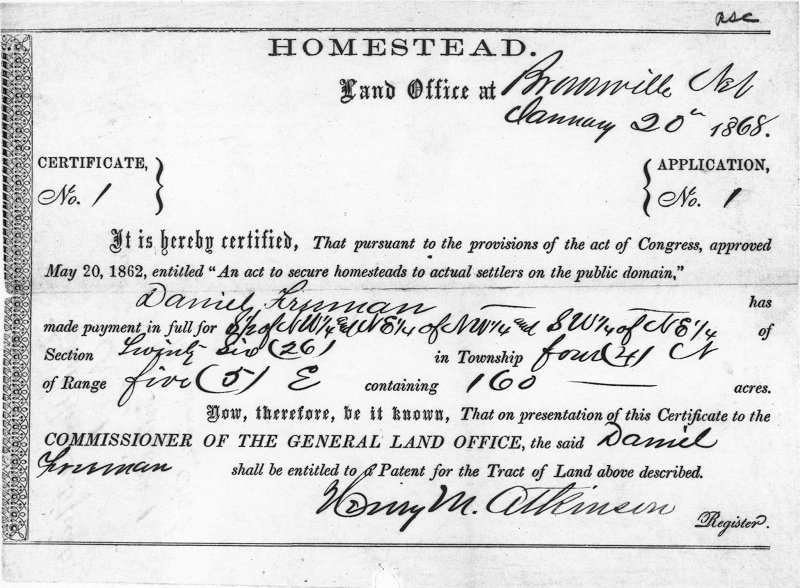

Looking specifically at free wireless access points, Wifi-Hog is also a reaction to the public spaces they inhabit. Wifi-Hog is a personal tool to enable both private interaction in public space as well as social obstruction and deconstruction of shared resources. The idea has some historical precedent in the area of property acquisition prior to the introduction of state-controlled zoning laws, when at the time land was a public resource that had to be regulated due to misuse and territorial disputes. An example of this type of territorial dispute occurred the United States in the late 19th century. The Homestead Act of 1862 provided that unoccupied public land be transferred to a homesteader after five years of residence. This was an act sanctioned by the US government to create a system of land grants to encourage settlers to develop the then uninhabited West. In effect, the Homestead Act was a pay off for settling in the region.

“Homestead Deed”, 1868.

My aim with Wifi-Hog was to investigate how wireless networks could fall into this predicament since they can leak or pervade from private to public spaces. Imagine if you had lived on the land for 3 years, it was still in the public domain, but you had invested your life into it, and someone came along and fenced off the land with a barrier you could not penetrate. In this case you do not have any legal right to the land, but you still feel as if it is yours since it has been in your custody for 3 years. This is a scenario closely linked to Wifi-Hog’s premise that a public wireless network maybe be partially owned or controlled by someone, but it can nevertheless be taken away and controlled. This containment issue might also allow for third parties to disrupt or interfere with them. The project is intended, thus, to send a clear message to groups attempting to claim ownership over a public space by demonstrating that their network can be easily jammed and controlled by others. An example of its use might be for an individual to use Wi-Fi Hog to disrupt a corporate signal and let a weaker, but free node exist in the same space. This signifies a loss of control by providers and sparks a challenge to their “land-grabbing” attitudes.

Since the project was introduced, most of the reaction from the wireless and media arts communities has been negative. This mostly stems from misunderstandings of why the project exists and how it was presented. Most people were upset that I was “advertising” the PVJ as something that could disrupt all of the progress and work that had been done to create open networks. My focus at first was to disprove the fact that wireless was leading us into a “utopian” world where networks would be everywhere and people would work harmoniously beside each other. I see this as a simplistic view that fails to see the conflicts of ownership and the complex integration and use of wireless in public spaces. Some thought that my project created rifts in the “community nodes” that existed such as London’s Consume.net or NYC Wireless’s wireless parks, since I was promoting a disruptive tool. From a discussion on the NYC Wireless list, some comments about the project were made evident by an anonymous poster:

“If I remember the way NYC Wireless, etc started out, the very act of putting up public wireless nodes was to exert territoriality – we were claiming the public parks as free Wi-Fi zones, and betting that these would deter pay providers from locating there. To a large degree this has turned out to be an accurate prediction. We were also trying to re-contextualize networks within local places, grounding them in real urban communities rather than having them exist in some kind of an abstract non-geographic cyberspace. I have to agree that this project doesn’t seem to be terribly sophisticated, and is very reactionary. It is a yes/no proposition, without any selectivity. You might just as well just be climbing atop the maintenance shed in Bryant Park and plugging / unplugging the antenna lead.“ (August 2003)

Despite the mixed reactions and confusion surrounding the point of the project and its execution, the problem it addresses remains important. As spectrum overcrowding becomes more common in cities, the conflict between for-pay and free nodes will reach a critical point. Companies will have to enforce strict delineation of their signal strength so that free networks cannot impede on their business models and vise versa. Projects like WiFi-Hog are clear and critical reminders that wireless networking is still a young technology that displaces architectural and social boundaries. This distinction is important for the future of wireless and the communities that support its development.

References

- Slashdot, August 2002 (http://yro.slashdot.org/yro/02/08/20/0431202.shtml?tid=98)

- NYC Wireless (https://www.nycmesh.net)

- WARchalking (Wireless Access Router) (http://www.warchalking.org)

- NetStumbler (http://www.netstumbler.com)

- Noderunner (http://www.noderunner.com)

- Blast Theory, “Can You See Me Now?”, (http://www.canyouseemenow.co.uk)

- Carnivore, (http://r-s-g.org/carnivore/).

- Consume.net (http://www.consume.net)

![]()